The German gestured to me that we all would be hanged

Stáhnout obrázek

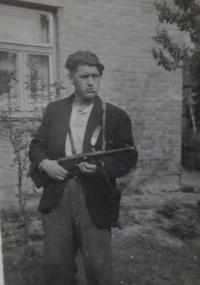

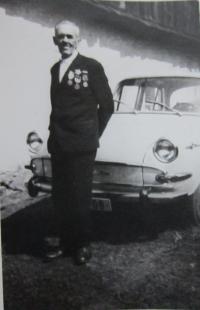

Amálie Fojtíková, née Rafajová, was born in 1929 in Koliby, a community of clearing owners and part of the Rajnochovice municipality in the Kroměříž district. The community is situated in the middle of Hostýnské Hills, and the environment was perfect for guerrillas during the war. The units of the 1st Jan Žižka Czechoslovak Guerrilla Brigade operated in the area from 1944 and the witness‘ family supported them in all possible ways. František Řepka and Vladimír Řepka, her uncle and cousin, respectively, even joined the guerrillas. In the winter of 1945 the ZbV Kommando 31 anti-guerrilla unit came to Koliby and everybody was arrested, and houses plundered and burned. Fifteen year-old Amálie, her minor brother František, mother Amálie, and stepbrother Josef Češek were in prison until the end of the war. Amálie and her brother František were released three days before the arrival of the Soviet Army, and Josef Češek and mother Amálie escaped from prison during a transport in May 1945. Aged sixty, the father of the family hid in the mountains for several months. The community of Koliby was not restored after the war and madam Amálie eventually moved to Vítkov where she lives to this day.