As a kulak kid, I had to work at the pigs

Stáhnout obrázek

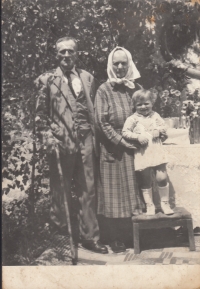

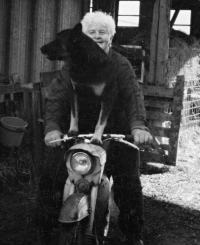

Alžběta Ešnerová was born as Burešová on 11 June 1937 in Trpín in the Českomoravská vysočina. Her parents farmed a rented farm there. She was one of eight children. She spent the end of the German occupation in neighbouring Kněževes. In 1946, the family moved to Hradec nad Svitavou and farmed a large estate left by the displaced Germans. After February 1948, the parents faced pressure to join a unified agricultural cooperative. Under the threat of immediate eviction to the Šumperk region, they finally gave in. As a peasant child, Alžběta could not even choose a field of study. She attended a one-year apprenticeship for pig breeders in Velké Pavlovice in the Slovácko region. Then she found a job on a state farm in Lubenec in western Bohemia. She worked in cowsheds and pigsties in Skytaly, Chýš, Velečín and Pšov. She married and had two children. In 2023, she lived in the settlement of Kobylé in Pšov in Žlutice. The memoirs of the witness were filmed and processed thanks to the financial support of the Karlovy Vary Region.