It‘s horrible to see a dead child or a woman killed by a grenade

Stáhnout obrázek

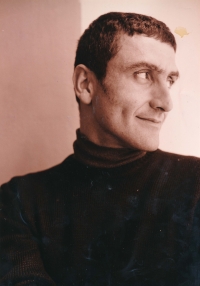

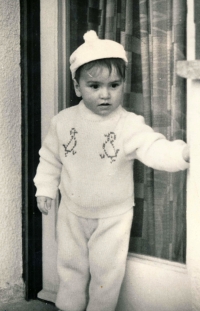

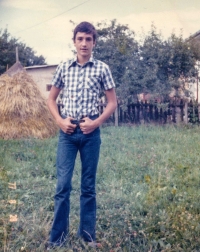

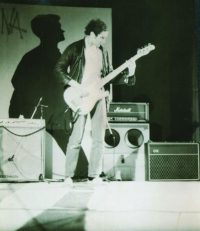

Petar Erak was born on 19 October 1963 in Bugojno, central Bosnia and Herzegovina, into a Serbian family. In 1970, he moved to Sarajevo with his parents and younger brother, where he entered the elementary school. In secondary school he started playing saxophone in a student band Bolero. After finishing the secondary school, he completed a year of military service and then studied at the Faculty of Chemical Technology in Belgrade. In 1986, he returned to Sarajevo, married his classmate and started playing in the alternative rock band called SCH. The band toured throughout Yugoslavia, and in 1989 they released an album called During Wartime, which predicted the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In April 1992, Petar volunteered for the Bosnian army. He defended Sarajevo besieged by the Serbian army until September 1995. He left Sarajevo when invited to participate as a member of the SCH group in the Month of Bosnia and Herzegovina project, organized by President Václav Havel in Prague. He never returned to Sarajevo. His wife Nela joined him after the war in March 1996. Together they ran two cafés in Prague. After adopting a son, Petar became a lecturer in foster parent education. His wartime experiences are narrated by one of the characters in the 2017 Bosnian film „Men Don‘t Cry“, directed by Alen Drljević, who was one of the members of Petar‘s platoon. At the time of filming in 2022, Petar Erak was living in Prague.