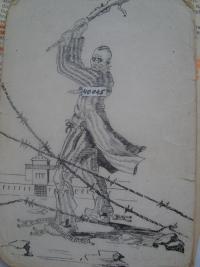

Where was God when they were sending children to the gas chambers in Buchenwald?

Stáhnout obrázek

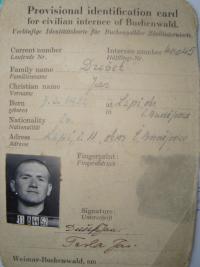

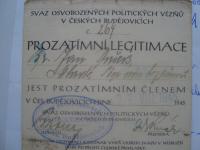

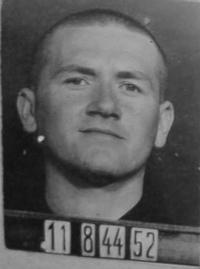

Jan Dušek was born on March 7, 1922, in Lipí near Budweis. Before the outbreak of World War II he became a mason and commuted to work in Budweis. He was arrested for the first time in Planá after he stole parts for a secret radio station from an airport construction plant. He was, however, released after three weeks of interrogations by the Gestapo. In 1940 he joined the illegal Communist resistance organization TRN. His main duties in this organization was to collect weapons and leaflets. On April 21, 1943, he was arrested again and taken to the Gestapo headquarters in Budweis. From there he was transferred to the Pankrác prison after six months of investigations. He only stayed one week in Pankrác and was then taken to the Theresienstadt Concentration Camp in the autumn of 1943. In his first concentration camp he worked as a mason and in the, „schreibstube“, (for receiving new camp inmates). In May 1944 he was transferred to Buchenwald where he became a member of the illegal international leadership of the camp, a member of the Hundkommando, that was training dogs for war, and a member of the Lagerkommando, that was receiving and transporting inmates. In 1944 he experienced an allied air raid which left him with a life-long injury. He was sent on a death march on April 5, 1945. The inmates on the march were liberated by the U.S. army on April 12. He returned home in June 1945. After the war he worked for the police. Currently he lives in Jindřichův Hradec. Jan Dušek has been permanently scarred by his terrible experiences and suffering in the concentration camps.