Bohuslav Čtvrtečka‘s heart beats for Škoda

Stáhnout obrázek

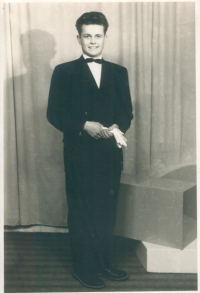

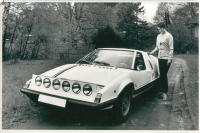

Bohuslav Čtvrtečka was born on 13 December 1943 in Kvasiny in the Rychnov region. He devoted his entire career to the local car factory. He started from scratch and after 46 years ended up in a top management position. His uncle, father, wife and daughter worked at Škoda and his grandson still has been working there. In the early 1970s, he helped to start the production of Škoda Octavia in Chile. He has seen the ups and downs of the car factory and Škoda is his life. He still does guided tours of plant in Kvasiny and he is an active member of the veterans association. He lives, where else than in Kvasiny, just a few hundred meters from the car factory.