“In 1949 the Jewish population in Israel doubled in contrast with the previous year. Those who experienced it will never forget about that. It will never be repeated again.”

Stáhnout obrázek

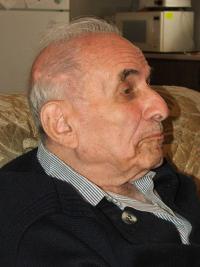

He was born in a German speaking Jewish family in Olomouc. His father worked as a professor at a German Grammar School. Zwi Batscha was active in Zionist Youth Movement. He left for Palestina in 1939. He was in kibbutz at Lake Genesaret during the war. After the war he came to Czechoslovakia for two years. Under his pseudonym Bedřich Seidemann he organized the departure of Jews from Czechoslovakia to Israel in 1947-1949. He studied philosophy and became a professor of political philosophy at the University of Haifa. He lives in kibbutz Kfar HaMaccabi not far from Haifa.