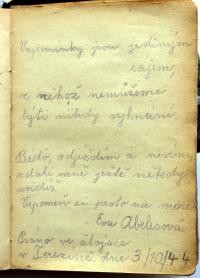

None of my girlfriends has returned

Aviva Bar-On was born in 1932 as Bedřiška Winklerová in a Jewish family in Miroslav near Brno where her father owned a sawmill. After the occupation of the Sudetenland Miroslav became part of the German territory and the family fled to Brno to stay with their relatives. In 1942 the entire family received the order to board transport to the Terezín ghetto. While in Terezín, Bedřiška‘s mother worked in a mica factory. Due to her youth, Bedřiška was not admitted to the Kindersheim and she thus stayed together with mother. At the beginning of February 1945 the whole family left Terezín in a special transport to Switzerland. The Winkler family passed through quarantine and then awaited the end of the war in Switzerland. In July 1945 they returned to Prague together and they continued to Miroslav soon after. In May 1949, Bedřiška and her brother Felix made use of one of the last opportunities to leave Czechoslovakia legally and they emigrated to Israel. At first she lived in a kibbutz, then she studied a course for nurses and later she graduated from sociology. In 1956 she married Asher Braun (Bar-On) who came from Hungary. She has three children and eleven grandchildren. Aviva Bar-On lives in the town Kiryat Ono near Tel Aviv.