A childhood under National Socialism

Stáhnout obrázek

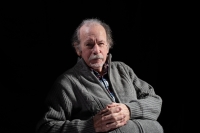

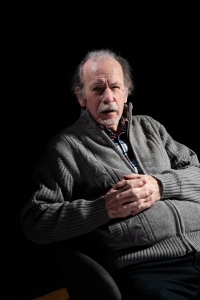

Hartmut Topf was born in 1934 in Berlin. His father was Albert Topf whose cousins led the family business “Topf & Söhne” during the time of the National Socialist regime. This company played an important role in the development of special crematoriums for concentration and extermination camps. Albert Topf himself was an engineer at Siemens and member of the NSDAP. In April of 1945, he was sent on an assignment of the Volkssturm, a militia that conscripted mostly older men and young boys that hadn’t been previously drafted as soldiers. This is why his wife and three children witnessed the arrival of the Red Army in Berlin without him. After the war, he returned to his family after having spent a few weeks in Soviet captivity, but only for a short period of time. In summer of 1945, he was summoned to a police questioning and subsequently abducted and imprisoned in the NKVD special camp Sachsenhausen where he died in 1947. Meanwhile, Albert Topf’s son Hartmut went to school where he got in trouble for secretly distributing leaflets that were critical of the GDR and the Soviet Union. After he was caught, he managed to escape to West Berlin. In West Germany, he worked in various jobs until he become a journalist. Early on, Harmut Topf started to research the family history. He started publishing his findings in the 1990s and has been an open advocate for the establishment of a memorial in Erfurt on the former premises of “Topf & Söhne”, informing about the intricate entanglement of the company with the Holocaust.