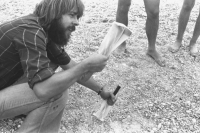

Even before Austria and West Germany signed the contract with Czechoslovakia about breaking the Iron Curtain, we de facto broke it in this great way

Stáhnout obrázek

Ladislav Snopko was born on December 9, 1949 in Košice. After finishing the secondary school, he studied medicine in his hometown for a while, but as he inclined to the archaeological profession, he decided to enrol at the one-year practice in archaeological research of Devin Castle. Afterwards he decided to focus on this field of science. In 1970 he was accepted for the study at the Department of General History and Archaeology at the Faculty of Arts, Comenius University in Bratislava. He was successful and graduated in 1976. While studying at the university he met many eminent personalities of Slovak culture, science and politics. They used to organise various cultural events such as Koncert mladosti (Concert of Youth), Blues na Dunaji (Blues on Danube River), Folkfórum (Folk Forum), Gitariáda (Guitar Music Contest), which usually didn‘t correspond to the cultural policy of the regime, therefore they were under strict control of the State Security. Ladislav Snopko also contributed articles to various magazines, lead an archaeological research and historical reconstruction of the ancient site of Gerulata in Rusovce near Bratislava, and in years 1988 - 1989 he was the head of the secretariat in organisation called Kruh priateľov českej kultúry na Slovensku (Circle of Friends of the Czech Culture in Slovakia). During the revolutionary days in 1989, he was one of the founding members of the Public against Violence movement (VPN), which was officially established as the most important opposing force of the Velvet Revolution in Slovakia on November 19, 1989. On December 10, 1989, he and Martin Bútora organised a march under the slogan „Hello Europe“, during which thousands of Bratislava citizens passed through the open Iron Curtain to Austria. From 1989 until 1991 when the Public against Violence ceased to exist, he worked as a member of the movement‘s crucial body, the Coordination Centre. In the years 1990 - 1992 he was a Minister of Culture of the Slovak Republic, the member of the Slovak National Council and the chief coordinator of culture, education, sports and tourism of the Central European Initiative countries. He was also a founder of the cultural fund called Pro Slovakia, magazine Profil súčasného výtvarného umenia (Shape of Contemporary Visual Art) and worked as a member of the council of Bratislava self-governing region.